“When Jesus landed and saw a large crowd, he had compassion on them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd. So he began teaching them many things.” – Mark 6:34 (NIV)

The question to ask is not whether it is realistic or practical or viable but whether it is imaginable. We need to ask if our consciousness and imagination have been so assaulted and co-opted by the prevailing consciousness that we have been robbed of the courage or power to think an alternative thought … the imagination must come before the implementation.”

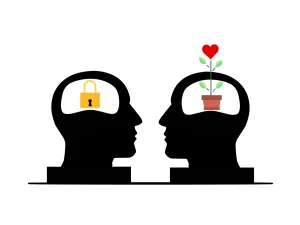

The Christian mind, at its heart, is called to transcend mere practicalities and embrace the vast horizons of imagination and creativity. It begins not with a blueprint for a better world but with a vision of that world seen through the lens of divine possibility. Imagination, in this sense, is not escapism but a courageous act of faith—a refusal to accept the status quo as inevitable and unchangeable.

Creativity flows from this imagination, forming the very substance of what it means to live in alignment with the Kingdom of God. It is the act of participating in the divine narrative, weaving threads of hope, mercy, and justice into the fabric of human existence. A Christian imagination does not shy away from the brokenness of the world but seeks to envision redemption within it, crafting solutions that are as inspired as they are transformative.

Without imagination, faith risks becoming containment—bound by tradition and limited by convention. But when infused with creativity, faith inspires bold action, challenging systems of oppression and envisioning communities of radical love and grace. The Christian mind must therefore be a fertile ground where imagination blooms and creativity transform, echoing the divine mandate to “make all things new.”

The big lie is to tell ourselves, “The need is too great, the areas of need are too dangerous, and I am too helpless to do anything about it.” We then excuse ourselves from doing anything. The well-known story of the good Samaritan tells us that he only helped one person, but that he helped him properly. The need in our country is great, but just helping one person properly can make a huge difference to that person.

Millions in South Africa remain the victims of injustice through forced evictions. I think of the ganglands on the Cape Flats. These were people who lived in town, in reasonable houses and with a strong community leadership. Now torn from their homes and slung out into those compound-like flats new leadership structures emerged and suddenly a violent gang culture with drugs the new currency emerged. We call them by many names, forgetting they are the victims of one of humanities greatest injustices. Right here on our doorstep.

Compassion emanates from the deepest parts of our being—from emotional responses, cognitive reasoning, and spiritual inclinations. It is not passive sentimentality; it is active engagement, a discipline that asks us to see others as they truly are and respond with love and care. To cultivate compassion is to align our minds and hearts with the profound truth that every person we encounter carries a story, a struggle, and a longing to be known. In this way, compassion reshapes both the giver and the receiver, making the world a kinder, more connected place.

This is the mind of Christ: seeing people not through the lens of performance, politics, or category—but through the lens of mercy. He doesn’t just see what people do; He sees what they carry. Their fear. Their confusion. Their longing to be known and healed.

Christ’s compassion was not sentimentality. It moved Him to action: He taught, healed, fed, and forgave. Compassion, in the mind of Christ, is never passive. It leads us to show up, to speak gently, to act justly.

To cultivate a compassionate mind, we must ask Christ to show us how to look at others as He does. Not merely with human sympathy, but with divine vision. Where we feel nothing, we ask for tenderness. Where we feel judgement, we ask for understanding.

The mind of Christ is not quick to condemn but quick to care. It recognizes that each person is fighting a battle we cannot fully see.

Michael Crockett has been working in Hanover Park since 2015, particularly among the Mongrel Gang, where he assists in feeding through the Winter, makes time for games with the children, makes use of the Early Childhood Development information. The aim is to break the chain from childhood to gangsterism.